HURRICANES

2017 was the year America’s hurricane luck ran out.

For much of the decade that began in 2010, hurricanes with winds of 111 mph or more flirted with Florida and other parts the United States, but never made landfall. In fact, not one major hurricane hit the U.S. between 2006 and 2016. Colorado State University hurricane scientist Phil Klotzbach called it “an amazing streak of luck.”

Then came 2017. Three powerful hurricanes — Harvey, Irma and Maria — slammed into different parts of the country, causing $265 billion damage in four weeks.

“We set an alarming number of hurricane records in 2017,” MIT hurricane scientist Kerry Emanuel said.

Harvey parked itself over Houston and unleashed a downpour. It killed 68 people and set a U.S. record for amount of rain recorded from a storm: 60.58 inches. Harvey’s $120 billion in damages ranks as the second-costliest U.S. storm behind only Katrina in 2005.

Hurricane Irma came next and stayed at maximum Category 5 strength for the longest time ever recorded. Irma was the second-strongest storm recorded in the Atlantic, and it devastated the Caribbean and plowed into Florida. Irma’s $50 billion in damages ranks fifth.

The most devastating came last: Hurricane Maria leveled parts of Puerto Rico. Experts still can’t agree on how many people died, with some estimates in the thousands. Maria was America’s third-costliest storm at $90 billion.

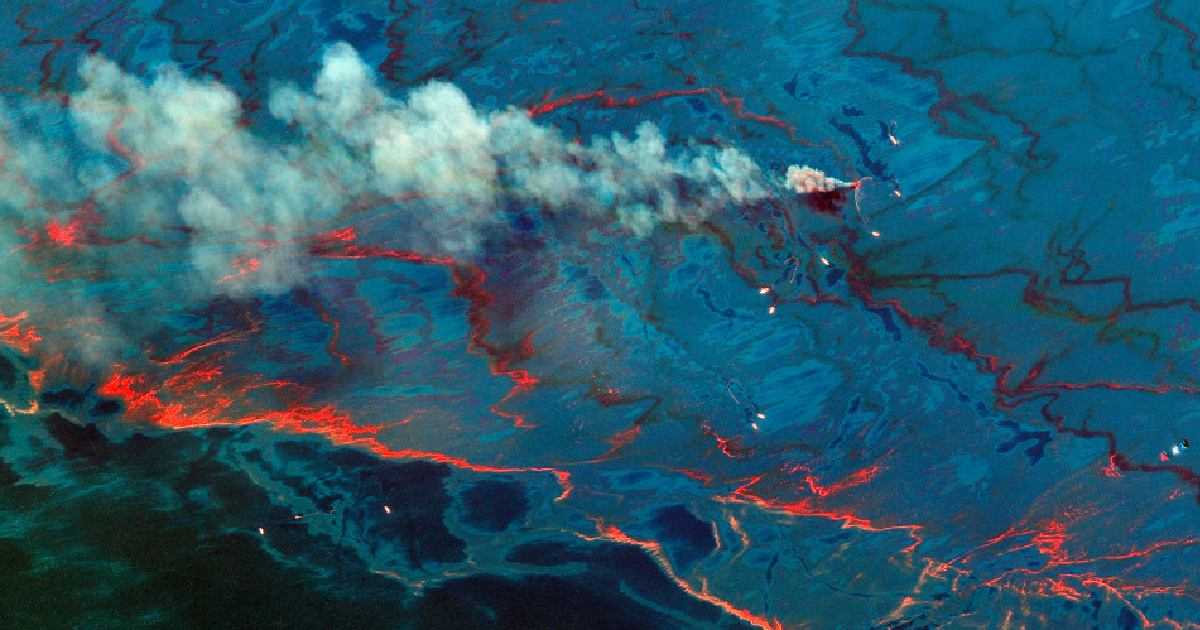

BP OIL SPILL

America’s biggest offshore oil spill began with an explosion that killed 11 people. It happened April 20, 2010, on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, which was extracting oil for BP. The rig sank two days later on the 40th anniversary of Earth Day. For 87 excruciating days, oil gushed into the Gulf of Mexico as people including oil engineers, a Nobel winning scientist and actor Kevin Costner came up with plans to plug the leak that left a bathtub-like ring of coagulated oil on the seafloor.

A team of scientists calculated that 172 million gallons spilled into the Gulf. BP said the number was closer to 100 million gallons, and a federal judge ruled that 134 million gallons had spilled. The case languished in court until April 2016, when a federal judge approved a $20 billion settlement, ruling that BP had been “grossly negligent.”

By then, the surface of the Gulf of Mexico had no visible scars. Beaches and marshes looked oil-free and back to normal.

However, scientists noticed an increase in dolphin deaths, which had averaged 63 a year before the spill. After the spill, they hit 335 in 2011 and averaged 200 a year for five years. Biologists also reported far fewer numbers of endangered Kemp Ripley sea turtles for years after.

GLACIAL MELTING

Earth’s glaciers have shrunk by about 3,860 billion tons (3,500 billion metric tons) this decade, according to research by Michael Zemp at the World Glacier Monitoring Service. That’s about 924 trillion gallons of melted ice and snow — enough to cover the United States in water 14 inches (35.6 centimeters) deep.

Glaciers in Greenland, including the Petermann, started the decade losing about 54 billion tons (51 billion metric tons) of ice a year. It slowed to about 37 billion tons (34 billion metric tons) in 2018 before speeding up again in 2019. Glaciers in the Southern Andes lost about 37 billion tons (34 billion metric tons) a year in the early part of the decade, and by 2018 they were losing nearly 47 billion tons (42.5 billion metric tons) a year.

“The last decade has been devastating for Earth’s glaciers and ice sheets, and unlike anything modern humanity has seen before,” ice scientist Twila Moon of the National Snow and Ice Data Center said in an email. “Communities have lost drinking, agriculture and hydropower resources as small glaciers have in some instances completely disappeared. Sea level rise from ice loss across the globe has increased flooding, coastal erosion, and health and safety problems, impacting people’s lives, communities, and economies.”

ROHINGYA EXODUS

In August 2017, Myanmar’s military launched a brutal, sweeping crackdown against the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority, burning villages, methodically raping women and girls, and killing thousands, including children. Human-rights groups have described the assault as a calculated campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide designed to drive the Rohingya from the Buddhist-majority country.

The bloodshed forced more than 700,000 Rohingya to flee to neighboring Bangladesh, where traumatized survivors crowded onto a stretch of low, rolling hills that would be transformed into the world’s largest refugee camp.

That is where they have languished for more than two years in cramped, squalid conditions amid a maze of bamboo-and-tarp shelters that do little to protect them from monsoon rains and stifling heat. Along with fury and fear, a sense of futility swept through the camps as the survivors’ pleas for justice went unheeded despite an international outcry over Myanmar’s actions.

In November, the Rohingya were given reason to hope: Myanmar was accused of genocide at the United Nations’ highest court. In December, Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi appeared before the International Court of Justice to defend her nation’s army from the allegations, arguing that the Rohingya people’s exodus was the unfortunate result of a battle with insurgents.

The African nation of Gambia brought the case against Myanmar on behalf of the 57-country Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

WILDFIRES

Looking down from space on Nov. 9, 2018, the outskirts of Paradise, California, glowed like burning coal. Hundreds of homes appeared as tiny embers. Entire neighborhoods blazed like bonfires.

The scope of the worst wildfire in California history hits home when seen from 300 miles above Earth.

What happened in Paradise has become a cautionary tale about the kind of devastation that is possible when erratic winds carry sparks across a warming planet.

Eighty-five people died. Some perished in cars on roads so choked by traffic they couldn’t outrun the flames. Roughly 19,000 homes, businesses and other buildings were destroyed.

The state’s largest utility, Pacific Gas & Electric Co., was blamed for the fire — one of dozens of blazes its equipment has caused in recent years — and forced into bankruptcy. A grim new reality emerged: widespread preemptive blackouts to stop power lines from sparking new blazes. Lawmakers approved hundreds of millions of dollars for firefighting and aggressive brush clearing to protect communities.

The fire has not led to limits on construction in especially fire-prone rural and mountainous terrain, where homes are more affordable. During a severe state housing shortage, a new Paradise is rising from the ashes.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ISLAMIC STATE GROUP

The Islamic State group emerged in 2014 during chaotic conflicts in Syria and Iraq. The militants seized towns and cities, quickly gaining control of one-third of both countries. IS created what no other extremist group had before: a so-called Islamic caliphate, with the Syrian city of Raqqa as its capital. Thousands of foreign fighters converged there, and the militants ruled over the local population with a mix of terror and rewards. They levied taxes and extorted the local population. They smuggled oil and collected ransoms, making IS one of the richest militant groups to ever exist.

The group also plotted and executed attacks in the West. It produced thousands of slick online propaganda videos and recruited supporters around the world.

In response to the threat, a military campaign by a U.S.-led international coalition slowly chipped away at the group’s territory. The militants made their last stand in March 2019 in a tiny Syrian village on the border with Iraq.

Even though IS has lost most of its territory, the group remains a threat in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and beyond. Its shadowy leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was killed in a U.S. airstrike on his hideout in Syria in October. But a successor was named, and pledges of allegiance came in from militants in Asia and Africa. Thousands of IS supporters and family members from all over the world, including children, are imprisoned in Syria.

ARAB SPRING PROTESTS

A young Tunisian fruit vendor, frustrated at what he said was a system that trapped him and others in dire poverty, set himself on fire in December 2010. His death spurred calls for demonstrations throughout the region and started a movement that spread though social media and satellite TV.

People took to the streets with varying degrees of success, and the months that followed became known as “The Arab Spring.” Protests reached fever pitch in Libya, Egypt, Syria and Yemen.

Calls for basic human rights, the departure of autocratic leaders and a way out of the poverty and unemployment for much of the region’s youth were central to demonstrators’ demands. But the movements were decentralized and lacked clear leadership. Still, they generated enough momentum to topple longtime presidents Hosni Mubarak of Egypt and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia.

In Libya, Sudan and Yemen, the uprisings laid bare existing divisions in society that sparked civil wars that continue to this day. In Egypt, pro-democracy demonstrators saw their gains reversed by a military-backed government that brutally suppressed dissent. In Syria, the government’s attempt to quash the protests led to years of civil war that devastated much of the country, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and uprooted millions. Tunisia remains the movement’s tentative success story, with a peaceful post-uprising transition and democratic elections.

Almost 10 years later, the region is experiencing a second wave of protests in countries that missed out the first time around. Earlier this year, demonstrations in Sudan and Algeria pushed out presidents after decades in power. In Iraq and Lebanon, protesters are calling for an overhaul of the political system.

JAPAN EARTHQUAKE – FUKUSHIMA

A magnitude 9.0 earthquake and giant tsunami struck the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Japan on March 11, 2011, causing its key cooling systems to fail, resulting in the meltdown of three reactors and spreading radiation into surrounding communities and out at sea.

Concerns about radiation at one point displaced about 160,000 people, splitting many families and communities. More than 40,000 still have not been allowed back.

The plant has since been stabilized and is being decommissioned, and officials say that could take decades. Removing the estimated 800 tons of melted debris and cleaning up the complex is an unprecedented challenge, some experts say. If or when the task can be done remains in question.

The scrutiny that followed revealed poor risk management practices by the government and plant operators and shed light on the lack of safety measures, prompting the public’s distrust and contributing to widespread anti-nuclear sentiment. Japan temporarily shut down all reactors for safety checks and introduced stricter safety standards. The approvals take time, and a handful of reactors have since been restarted.

The Fukushima disaster has chilled the nuclear industry around the world. In Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe still promotes nuclear energy as a key component of the nation’s energy mix, but the government had to largely abandon plans for nuclear plant exports and business overseas.

CHINA EXPANSION – SOUTH CHINA SEA

Across the sprawling and strategic South China Sea, nearly 70 disputed islands, reefs and atolls are occupied by five claimants. China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia have built airstrips, harbors, barracks and other infrastructure for both civilian and military use. Only China has created new islands by piling sand and concrete atop coral reefs.

That has upset the balance of power in the region, strengthening China’s claim to the entire waterway. It also has further harmed the fragile environment already threatened by overfishing, pollution and the harvesting of giant clams by Chinese fishermen.

Starting in 2013, China began dredging sand on a massive scale to build its seven new island outposts, creating 3,200 acres (1,295 hectares) of dry land.

Fiery Cross Reef is among the most extensively developed, boasting large facilities for aircraft, missile batteries and marine forces. Whether or not these islands make a difference remains to be seen, however. Not only are they exposed to the marine environment, but as Japan learned in World War II, holding and supplying remote marine outposts during a conflict can be a tricky proposition, particularly in a region where Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, the U.S. and others have shown a willingness to defend their own interests; territorial, economic and otherwise.

Weekly Bangla Mirror | Bangla Mirror, Bangladeshi news in UK, bangla mirror news

Weekly Bangla Mirror | Bangla Mirror, Bangladeshi news in UK, bangla mirror news