By M. Sophia Newman:: This weekend, Bangladesh celebrated Language Martyr’s Day once again. The holiday is one of my favourites – a celebration of the genuinely beautiful thing that brought me to Bangladesh in the first place. Yet I am too afraid to celebrate.

In 2011, I came to Dhaka on a scholarship for ten weeks of intensive Bangla-language study. In 2012, I returned for another ten-week round at the same institute, this time under a Fulbright fellowship. For those five months, I studied Bangla up to 70 hours a week, finally attaining an “advanced low” ranking on an international exam. The experience altered my brain – stretching and reshaping the way I think about words, a boon to any writer.

It spoke to my heart, too – I realised that the institute was sharing an essential component of the national character and ethnic identity. The window they provided into the Bangla language showed a rich history: Nazrul Islam, Rabindranath Tagore, and the fierce, victorious bhasha andolon. I had wished to come to another country and speak the local language, rather than asking others to speak my own. I thought of this as a kind of eradication of destructive colonialism – perfectly in key with the Language Movement’s dreams of an independent nation. I realised that my Bangla education was a tremendous privilege toward that goal.

Along with my gratitude though, was deep concern. Over time, it made me stop speaking Bangla entirely. It was simple, in the end: it feels too unsafe.

To learn a foreign language as an adult isn’t easy. Arriving in Dhaka at age 28, I found myself a young child again, slowly copying each new letter and conjunct, speaking in telegraphic two-word sentences. It was hard, error-prone work. The raw focus wasn’t the hard part though, nor the humility the effort imposed. The problem was hostility.

“Everything you say sounds like a joke,” a colleague once said about my accent. Another time, a family friend interrupted me to snap, “When you speak Bangla, it sounds like you’re speaking Russian.”

“That’s Polish, get it right,” I nearly yelled back, hearing the voices of my Polish-speaking grandparents echoing in my mind. I didn’t say it. But his xenophobia made my exhausting effort to learn the language feel pointless, even self-destructive. It hurt.

Every foreigner faces that though, and not just in Bangladesh. Hari Kondabolu, an American comedian whose parents emigrated from South Asia, says, “It’s hard having an accent in this country” (meaning the US).

“When maybe my father says something and he walks away, the idea that people are laughing because what he said is funny to them because of how he sounds crushed me.” My colleague and family friend are members of a worldwide tribe of language-policing jerks.

But if ridicule was the only problem, it probably wouldn’t stop my speaking Bangla. In fact, I would celebrate Language Day in defiance. As it is though, there’s no joy to be had.

“If I speak Bangla,” I once said to a Bengali man I trusted, “I think men here will treat me very badly.”

“Yes, they will,” he said looking grave. A moment of silence hung between us, and I realised that my gut sense was right. The problem isn’t just a disdain for accents.

The people who ridiculed my accent were male. Both also sexually harassed me. One felt entitled to say rude things about my body, although he stands out mainly for giving a sinister smile when rape was mentioned in a professional conversation and saying, “That happens to every woman here,” as though raping women delighted him. It made me feel like vomiting.

The other one – the “friend” who barked that I sounded Russian – sent me pornography by email, horrifying me. (To think of it now literally makes my heart hurt.) Angry that I refused to submit to his degrading demands, he later verbally abused me so ferociously that I nearly called the police on him.

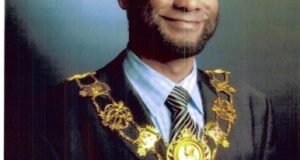

This second man was the grown son of a winner of the Ekushe Padak. The award honours elites, but also commemorate martyrs who preserved the richness of the Bangla language at great cost to themselves. It represents the same feeling of respect I had when I began studying Bangla. But my willingness to try to live in Bangladesh and function in its language meant that the inheritor of this tradition felt entitled to insult and harass me, as though cruelty was the birthright of Bangladeshi men. I felt scared, but also crushed at how he dishonoured his good father.

Both those guys weren’t the worst of it though. That came at the Bangla Language Institute.

On the first day of class in 2012, I worked with an instructor one-on-one. (All the other students were learning how to read; I had been there before, and already knew how.) Together, we read an essay he’d written about rural Bangladesh. It was a litany of difficulties — the woman in the story waited on males from daybreak to midnight, serving them food while going hungry herself. In the first paragraph, a sentence translated as “Even though the husband and the wife work equally hard, the woman has all of the responsibilities.” I asked what that meant, hoping I was failing to understand the words. But the teacher looked startled, muttered, and then admitted the sentence made no logical sense. He seemed to have failed to notice the full extent of the gender imbalance. His smile was strained, yet ominous.

It never got better. The teacher used lessons every week to present information about women being abused. When the class schedule mentioned “politics,” it meant a news story about a girl being shot. When it said we’d learn about tribal culture, he presented an article about tribal women being beaten.

“What do we know about women in Bangladesh?” he asked in that class.

“Basically nothing,” I replied.

I didn’t mean to say that I disbelieved the article. I’d found World Health Organization data saying nearly half of Bangladeshi women had experienced violent victimisation (tribal women included). I knew that there was overwhelming, long-running evidence of sexism and violence towards women here. What I could not understand was my Bengali teacher’s insistence on always speaking of women as victims of violence – and nothing else. The complexity of Bangladeshi female lives was flattened to nothing but rapes and beatings – an incredibly ugly picture of the country and a disservice to women in itself.

If he meant to speak out against that, he failed. He openly favoured the sole male student. He ignored women’s questions. I asked him not to force us to discuss violence; the next week, he deliberately wrote it into our exam. Later, after the course ended, he stalked me, creepily contacting me repeatedly by Facebook, LinkedIn, e-mail, and phone.

“Bangla-speaking women are treated badly,” his actions announced. “See, just like I’m treating you badly right now.”

“He is very patriarchal,” his supervisor acknowledged. He’d harassed another female student until she cried, she said. She also apologised for remarks he’d made that all white people should be forced to leave the country.

When I suggested at the end of the course that this teacher’s contract not be renewed, the director agreed. But then the institute rehired him. His privilege of abusing women, it seemed, was more important than their actual mission of advancing Bangla language.

The way these people behaved shaped my response to the whole nation. People ask why I say that extreme retribution towards Islamists isn’t a good idea. In part, it is because I believe the ongoing hartals, oborodhs, and counter-protests are entrenched destruction with no clear endpoint, and that revenge won’t help anything.

But I also know that people who support the ethnic nationalism and oppose Jamaatis are no saints. They will scream for grisly revenge against their enemies, but asking them to behave in kind ways towards their allies is often a waste of time. There is so much xenophobia and misogyny embedded in the culture that ethnic nationalists claim to defend that I can barely access it at all. To speak in terms of support for one side or another is not to make a moral choice; it is to choose between shadings of the same toxic hatred. It is to ask if I prefer the second-degree burn or third-degree burn, and then give both anyway.

There is a saying that a person will cry when they come to Bangladesh and cry again when they leave, first out of sadness over poverty, and then for love for the people. But I came to Bangladesh with hope, respect, and commitment to learning Bangla, and I left feeling so hated, endangered, and alienated that I could not bear to hear or read the language.

On this Language Day, I looked at my old Bangla books and felt pain, for foreign learners and for the language martyrs. I still can’t pick up those books.

“My father should be judged based on the content of his words and not the accent that comes with it,” Hari Kondabolu says. People like me should be allowed to speak too without being ridiculed, harassed, or harmed – and by that I mean all women, most of all, the ones living through violence in Bangladesh right now. I think my heart broke so badly in Bangladesh that I may never have the strength to return. I pray for women for whom it is home. For them, I hope common decency grows there.

Until that happens, we all might as well be speaking Urdu.

Sophia Newman, MPH, is a freelance writer. She completed a Fulbright fellowship in Bangladesh in 2013, and is currently reporting in Africa.

Weekly Bangla Mirror | Bangla Mirror, Bangladeshi news in UK, bangla mirror news

Weekly Bangla Mirror | Bangla Mirror, Bangladeshi news in UK, bangla mirror news